by SASHA HAJZLER (Infokolpa, Slovenia)

After the big E.A.S.T. assembly, we publish a text by Sasha Hajzler from Infokolpa, Slovenia who talks about struggles of migrants, women and workers along the Balkan route during the pandemic. Sasha explains how the pandemic has been the occasion to try to strengthen those visible and invisible borders that are part of the everyday lives of so many women and migrants living and moving along the Balkan route. The challenge to create connections between all those who are daily struggling against the government of migrants’ mobility and the intensification of care imperatives for women is key in the project of E.A.S.T., so much as the need to politicize solidarity in order for it not to be a service to the reproduction of society as it is, but rather a terrain of common struggle. The text has been published in coordination with Levfem and Lefteast.

Along with the immediate threat and damage to human lives, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic burst the door wide open to a global exercise of the politics of fear, surveillance technologies, war narratives, and tightening border policies, accompanied by financial instruments of control and other means of repression. As a result, the burden on countless precarious lives intensified. The world witnessed strikes, protests, direct action, the politicization of solidarity actions, and the interweaving of struggles tactics. The situation in the Balkans is not an exception. Below is a short overview of the struggles, but also a note on promising transformative actions along the Balkan route.

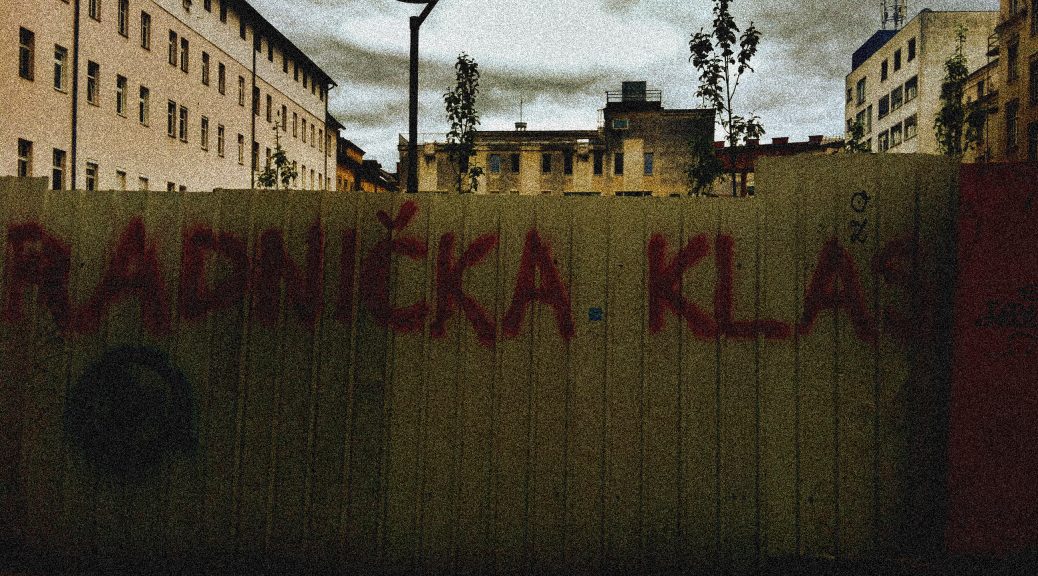

The height of the Covid-19 pandemic in the Balkans has brought to the light of day various exploitative government regulations, corrupt political and economic practices and debilitating restrictions on movement: from the lengthy curfew in Macedonia, municipality-localized movement restrictions in Slovenia, to the harshest confinements in migrant camps and detention centers everywhere. Like Germany and France, Slovenia also left the backdoor open to migrant labor, allowing entry for migrants with skills, predominantly in logistics, and in the industrial and agricultural sectors, not only widening the gap between “skilled” and “unskilled” people, but also intensifying the problem of treating people as mere labor, as tools, justifying their movement only when they move as servants of capitalism and neoliberal policies. Factories, nursing homes for the elderly, chain shops and hospitals became the primary points of tension where profit has been valued over life (as in the cases of the Lidl worker unions, the Gorenje factory in Slovenia, and textile factories in Macedonia). These as well as similar jobs depend strongly on systemic and structural conditions which are, even as the presence of the West varies among nation states, very similar throughout the region. Workers who have been laid off or pushed to work for employers’ profits are often a common sight in protests.

Reclaiming the freedom of movement goes hand in hand with reconceptualizing labor. Both concerns are inextricably tied beyond border and nation. Solidarity actions on behalf of activists were made for common visa and residence permit policies, but we must think how to confront and disrupt the logic that subjects people to these exploitative conditions in the first place. People who moved from Balkan & East Europe to the West/North/EU as a labor force are probably most aware of this issue, as some were unable to return home during the Covid crisis due to government policies restricting entry.

Such was the case for Serbian workers who for a while slept in cars in Slovenia where they worked in construction, since the Serbian government refused to timely open the borders for them. The responses of those showing solidarity toward them were similar to the responses to homelesness and relied on guerilla mutual aid and pirate care actions. Next, movement restrictions have also put additional strains on the concept of “the traditional family,” with an increase in rates of domestic violence. Just as a house is not necessarily a home, a home is also not always a safe place. Not only is there a chronic lack of proper regular housing in the region, but specifically safe houses are for many years now an issue on their own, affecting the lives of many, predominantly Roma, the homeless, the disabled, victims of domestic violence who are often women, children, and the elderly, LGBTIQ+ individuals, and migrants.

At the same time, we witness a firm continuity of action concerning the Balkan route: from reclaiming freedom of movement by crossing borders and demanding unconditional common residence permit to calls against patriarchal notions of women’s roles in the family. Within this sense, transnational practices of care and solidarity which transcend humanitarianism and operate in the realm of the political have merged during the pandemic. For the Balkan route struggles, just like elsewhere, women are at the front, fearing neither the visible nor the invisible border. These borders occur as tools, policies, places, laws, actors, and even ways of knowing. Let these abstractions not seduce the reader – they are not only concepts hanging high in the air – they have real-life consequences, often acting as violent borders do, bringing pain and death, but also raising resistance and enactments of bold political imaginaries. As care intrinsically carries power relations, processes of disciplining, skill and structural positioning, solidarity must be political: let us not forget that mutual assistance among the poor is in one sense quite welcome to governments, who can thereby shuffle off responsibility for the suffering that happens within their borders, encouraging the notion that care for others is a matter of private charity: a humanitarian, not a political, matter. Capitalist exploitation thrives on good humble people.

Knowing well that care must not remain only in the hands of “women as usual,” individual political will or humanitarianisms, but must as be alternatively institutionalized and politicized, feminist practices have proven key for illuminating and transforming visible and invisible borders. One prominent example of good political practice, besides Infokolpa, and also led by women, is the Transbalkan solidarity, where activists are focused on organizing, strategizing, direct support, action and common thinking in regard of the Balkan route: Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia and Slovenia. The practice is radical in its direct engagement with detangling and defying imperial, neocolonial, racial, patriarchal, cooptive violent regimes by agile (counter)action and common work, as a platform that connects different struggles, but also a political space of common sense-making that understands, recognizes and works with the differences. It is a political practice of prefigurative politics centered around the Political and politicized care.

The Transbalkan solidarity is also active with the campaign to raise the No One Is Illegal rainbow flag demanding that the EU provides shelter and protection to LGBTIQ+ people on the move throughout the Balkan route, and is also cross-pollinating with other initiatives such as Infokolpa, and further with Border Violence Monitoring, intensifying practices by interconnecting or, even confederating with other practices and movements in imaginative alliances. This is a promising response model to the needs of the present: combining the local with transnational. The above is especially relevant since after the global neoliberal protest movements against oppression, exploitation and inequality from 2019, governments have used Covid-19 to make many transborder and public-space actions and terrain work impossible. Such government policies have gotten their share of criticism, for example through protests, i.e. Friday protests in Slovenia, joining various blocks of struggles, ecology, feminist, anti-government, migrant – focusing on the increase of horrid deaths at the borders of Europe, as a consequence of the racist, discriminatory, fascist policies of EU, financed militarization, surveillance, all in the name of national sovereignty and state security – the same old adage from the power-thirsty propagandist machinery. Good examples of such propaganda found in government-produced military narratives praising nurses, care workers and doctors as our “soldiers, heroes, troops, and frontlines”. In Slovenia for example they were celebrated with cross-country flights, symbolically accompanied by US F16s, which have been used in many vile military operations around the world.

This narrative has to go. Health and life must not be abused to propagate militarization. In line with this, during and after the first Covid-19 outbreak there have been several records of symbolic acts of solidarity throughout the Balkan countries to contest and denounce such militarization, policing and other violence by the organs of oppression. Healthcare itself has been a separate issue in the region, especially for the most vulnerable groups: Roma, women, migrants, low wage precarious workers. Let us not forget that the savior doctors and nurses, as well as the health care bureaucracies who oversee them, also face (and execute) difficult decisions over who gets to live and who does not. It would be naive not to expect race, class, and gender not to play a role in these decisions on a systemic level. One brutal example was the death of a pregnant Macedonian Roma woman, who passed away due to belated and improper healthcare. Not so far away in BiH, a pregnant woman in labor with twins was denied hospitalization because she tested positive for Covid19.

And this pattern exists not only in the Balkans, but in the whole of Europe, there seems to be a political decision that elderly homes are last in line for medical aid, not surprisingly resulting in most of the deaths coming from the population stuck there. Just as this opened the question of political indirect euthanasia for the elderly, migrant deaths at the borders are becoming a sort of a death sentence comeback – in a way it evokes a death penalty, indirectly and sometimes (in cases of pushbacks) directly permitted or caused, merely for crossing the border of fortress Europe.

On that note, the implementation of public health measures in migrant camps and at borders clearly had little to do with Covid-19 and a lot to do with anti-migrant policy. Scenes of state violence toward migrant minors in detention centers have flooded the internet. Another proof is the much-discussed and highly contested border violence. Pushbacks are proving to be a systemic practice of EU-sponsored violence, repressive border regime, dehumanization, illegalization, and criminalization of people through organized, mostly violent operations of illegal collective expulsions of people across the green border, without giving them a chance to ask for asylum. People try to avoid getting caught and decide for dangerous crossings, that sometimes result in deaths on the border, or after, of exhaustion or illness. During the Covid-19 outbreak, militarization and the policing of borders were a staple suggestion in government-run measures. Repressive practices occurred as well inside the borders, let us remind ourselves of the example when in Serbia migrants were placed in a 24-hour mandatory quarantine and the military was deployed to monitor the curfew. Or when the covid-19 related lack of hygienic conditions and healthcare in the Slovenian detention center resulted with a protest of the people stuck inside.

This regional overview is the result of a two-year data-collection process. Data was collected from various sources (individuals, non-formal groups, organizations) in the field. Most outstanding in transnational organizing were migrant movements, which are inherently fundamentally questioning the abusive structure and violent nation-state system, connecting protests, global or regional or thematic approaches, and practices. The key is not only within prefigurative politics and building dual power, strategizing and thinking together, building a common discourse, making space for emergent movements, but also maintenance and repair work on the precarious daily life. We need to involve even more the migrant, labor, housing and women’s movements, translating struggles from local and “trans-” contexts, since during translation similarities and differences can be mapped and worked with, toward building an infrastructure of a more wise, just and solidary world.

Text prepared for webinar: (Post?)pandemic Struggles in Social Reproduction. Responses by Migrants and Women in Central/Eastern Europe and Beyond. TSS&LevFem

If you want to connect with E.A.S.T. project please write an email to: essentialstruggles (at) gmail.com or join the facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/343349476881958