by TRANSNATIONAL SOCIAL STRIKE PLATFORM

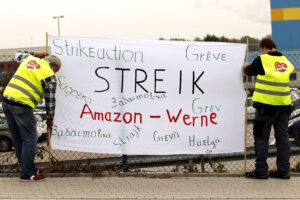

In November 2019, we published the journal “Strike the Giant! Transnational organization against Amazon“, just a few months before the beginning of the global pandemic. With this text we want to tell what happened in these months of struggle and revive the discussion on the issues raised in the journal, whose centrality seems to us confirmed and expanded. In the past months, in fact, the process of transnational organization of workers, which has been going on for years now insisting on the need to put in communication warehouses scattered throughout Europe and the United States, made a leap forward. The positions and common demands advanced by workers in struggle in the European and American warehouses and by Amazon Workers International against the danger of contagion, represented a real transnational insubordination, which forced Amazon to put in place a series of centralized responses. For the first time, Amazon and the workers it employs emerged as two opposing fronts with extreme clarity, preventing the giant of Seattle from finding local arrangements or from acting simply at the level of the single warehouse in order to hold back the protests and weaken the common demands. All this has shown that the transnational communication is by now ineludible and that an advancement in the level of the transnational organization is now at stake.

On March 17th, the warehouse in Piacenza, one of the areas most affected by the virus, went on strike for 11 days to denounce the non-application by Amazon of the anti-COVID measures approved by the Italian government. The warehouses in Turin and Rome were also hit by the protests. On the same day, a petition of workers from the DBK1 warehouse in Queens (New York) started to circulate and was promptly translated into various languages, collecting thousands of signatures within 24 hours from the U.S. and various European countries: France, Poland, Italy. The petition called for a series of immediate measures to deal with the emergency: sanitization of the plants, reduction of productivity standards, paid sick leave in case of need, bot due to personal causes and to the need to care for children or elderly parents, as well as protection for drivers.

Warehouses went on strike in France as well and everywhere those who could started to take a leave of absence or simply refused to go to work. For the first time the command to work was seriously questioned throughout the firm and Amazon could no longer guarantee delivery times. In Poland, pickers organized through Workers’ Initiative insistently asked for talks with the management, that were systematically denied. In Madrid, despite some workers tested positive inside the warehouse, Amazon did nothing to protect those still at work and the protests kept growing. While the number of cases continued to increase globally, the voices denouncing the absence of basic precautions became louder and louder on both sides of the Atlantic. The protest in American warehouses was expanding from Chicago to Minnesota, from Sacramento to Los Angeles to New York. A request was made for transparency on the numbers of positive cases inside the warehouses (which Amazon refused to provide) and on the plan of measures that the management intended to adopt. It was soon clear that not only the voracity of the management was preventing the introduction of distancing and sanitation measures, but the organization of work itself made impossible an effective prevention within the warehouses: the weary rhythms with very few pauses did not allow even to wash hands and the position of the various teams of package collection and delivery made the contact between pickers, stowers and drivers inevitable. This situation is widespread in the world of logistics, within which Amazon – which had built on its image of efficiency part of its success –, became a symbol in negative.

This situation forced Amazon to change its strategy also from a communicative point of view. The company began to present itself as a benefactor performing an essential service for the community and celebrating its workers as “heroes”. However, unable to calm down the rising protests, it was forced to respond directly from Seattle. In addition to the hiring of 100,000 new workers, Amazon announced a wage increase of two dollars/euro in all warehouses, not only American ones. While Amazon declared the need to face an increase in orders due to the explosion of e-commerce, it was obvious the attempt to calm the ferment that was crisscrossing the warehouses. Of course, the local differences were immediately defined: in Poland the bonus of 2 euro per hour became of 0,60 cent, in Slovakia of 1,5 euros. Nonetheless, beyond the usual policy of management of wage differentials, what is certain is that Amazon was forced to yield what it would never have yielded until that moment.

Against the attempt to sedate the protests through the wage increase, Amazon Workers International, collecting the demands that emerged transnationally during the protests, published a statement declaring the wage increase insufficient and rejecting the exchange between money and health that Amazon was trying to impose. Common and precise demands were made: not only the closure of warehouses due to the blatant absence of security measures, but also paid sick leave and the modification of standards to ensure more humane rhythms and to allow people to take care of their health. Strikes and protests continued throughout Europe. Faced with fears of warehouse closures while the pandemic was at its peak in many European countries, Amazon declared that in France and Italy it would only handle essential products: in fact, because of the growing demand for essential goods, Amazon ensured an unchanged or even increased flow of goods. The data on Amazon’s profits in recent months speak clearly: not only is Jeff Bezos the richest man in the world, but Amazon’s profits have literally doubled if compared to 2019. The concept of an essential good thus became, as it happened widely in the world of logistics, a gimmick to increase activities when they should have instead decreased.

In response to the strike, a “safety committee” was created in the warehouse of Piacenza, composed by union delegates and appointed for the control of security measures. The committee began to work with great difficulty and soon turned out to be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it was a way to govern the protests: the company showed thereby to observe the rules undersigned by the government, the industrial confederation and unions defusing the demands that were coming from the warehouse. On the other hand, the power of this committee risked to be almost nonexistent: it did not have a decision-making power, it limited itself to write periodical “reports”, acting more like an organ of control on the workers rather than on the management. It was the same for the “safety angels” introduced in France, that, despite the name, are a sort of watchdogs that make the work even more unbearable, an intention confirmed by the project to introduce surveillance devices in the warehouses that launch an alarm when two colleagues approach each other less than two meters. Amazon began to promote the idea that the workers themselves were responsible for the infection and for the failure to respect safety distances, perhaps in the (very few) breaks or in the canteens: this was also an opportunity to increase discipline inside the warehouses. Moreover, the rules around social distancing became an additional tool to hinder communication between workers.

In this situation, something unexpected happened in France. After numerous protests in various warehouses, also as a consequence of the

fact that Amazon refused to consider the right to paid leave in high-risk situation exercised by the workers as legitimate, and to discuss with workers’ representatives, the Solidaires union decided to sue Amazon. A ruling of the court of Nanterre first and of Versailles later sentenced that Amazon had to limit itself to the really essential goods – confirming that the previous declaration of a limitation of the flows was completely bogus –, to be transparent in communicating the numbers of positive cases and to plan a wide-ranging intervention to evaluate and prevent the risks in the warehouses. Due to the sentence, that dictated pricey fines in case of disregard of the prescriptions, Amazon decided to shut down all warehouses until the implementation of the new dispositions. With the lockout Amazon wanted to demonstrate to have a real control over its supply chain, from start to finish. Therefore all the logistics centers as well as the network of warehouses, both internal and external to the group in other European countries (Spain, Italy, Germany, Poland, Slovakia) were used to deliver to French customers, while the warehouses of the French subsidiary “Amazon transport” were used to carry on business as usual.

Against the attempt to make the measures introduced valid only on paper or temporarily, on April 30th Amazon Workers International published a letter to Jeff Bezos and Stefano Perego (general manager of Amazon Europe), as a result of a close confrontation between struggling warehouses on both sides of the Atlantic. The letter had two main objectives: to make permanent some of the measures introduced, such as the wage increase and the suspension of productivity standards; and to ensure transparency on the communication of the number of positive cases and on the measures adopted in terms of safety at work, which needed to be established through a dialogue with the workers themselves. The question on the agenda was, moreover, whether the measures introduced would go in the direction of increasing control over movements, to favor the imposition of greater flexibility and availability to work with the excuse of a reorganization of shifts, or whether it would be possible to counter the worsening of the conditions of a work already heavily wearing and dangerous before the pandemic. For this reason, returning to “normal” would mean putting everyone’s health at risk again. Also, for this reason the wage increase could not be an occasional bonus, but it had to remain. It is clear that no government protocol or trade union agreement addressed, during the months of the pandemic, the overall problem of wages and so-called “essential” workers conditions. Instead, the multiplication of regulations and norms allowed Amazon, as well as other companies, to continue to hide and make profits, often using them to their own advantage to strengthen command at work. Only the transnational organization pointed this problem out.

Furthermore, the letter displays with extreme decision the outrage for unjustified layoffs of the previous weeks. Amazon’s management has in fact used the new distancing rules as an excuse to leave workers at home who have raised their voices. In the United States, increasingly devastated by the COVID19, protests, strikes and “sick-outs” have multiplied, especially in those warehouses where the management has tried to hide the positive cases so as not to stop production. In response, Amazon began to dismiss indiscriminately some of the participants in the protests accusing them of violating social distancing measures. Chris Smalls in Staten Island, a foreman who rebelled against management’s instructions to keep quiet about the contagion cases in the warehouse, is fired for participating in a walk-out and accused of violating the quarantine imposed on him by the company. Bashir Mohammed in the warehouse of Shakopee in Minnesota, after having mobilized with colleagues and colleagues, is fired for having violated the distance while talking with a colleague in the parking lot. “They fired me to scare the others,” Mohammed said. John Hopkins in San Leandro was fired on charges of “endangering the lives of his colleagues,” as were Courtney Bowden and Gerald Bryson from the Staten Island warehouse who participated in the protests with Chris Smalls. In addition to this, two tech workers have been dismissed, Maren Costa and Emily Cunningham, organized in the collective Amazon Employees for Climate Justice, who have been vocal in their opposition to the company’s policies during COVID19 and in support of the ongoing struggles in the warehouse.

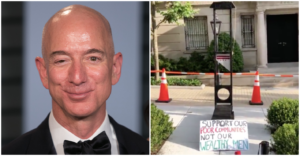

Right after the layoff of Chris Smalls, an internal e-mail exchange was leaked to the press, in which the management discussed how to deal with the strikes in the New York warehouse: one of the managers said that Smalls was stupid and not articulate, advising to smear him openly indicating him as the person responsible for the protest with the aim of diverting public attention from the insufficient security policies. Smalls is black, and the racist implication of this discussion is obvious. Shortly afterwards, the uprising following the murder of Georg Floyd broke out. A few weeks later, that very same manager published a letter expressing his deep antiracist beliefs. Together with him, Jeff Bezos threw himself into statements in support of Black Lives Matter, publicizing a donation of 20 million dollars to associations for the rights of African Americans (of which 8 actually collected through donations from his employees). And yet, it was no coincidence that all the pickers fired unjustly and for a pure intimidation strategy were black. The racism manifested in the police killings is the same on which Amazon bases its wage and business policy: while African Americans make up 15% of Amazon’s total workers, in fact, 85% of them work in warehouses. The urban planning studies made by Amazon before opening a new warehouse usually look for suburbs with a higher concentration of blacks and higher rates of poverty and unemployment to present the company as a benefactor against whom one can never raise one’s voice. After all, the Amazon Ring company – which provides cameras and apps to monitor private homes – has been working for years with the police and Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) to deliver facial recognition data. For all these reasons, Bezos’ twits in support of Black Lives Matter was inundated with insults, some of which very briefly expressed the heart of the matter: “if you are in favor of us Afro-Americans, then open your wallet!”. Amazonians United of Chicago by their side declared “If Amazon truly believes that Black Lives Matter, why would they cut the pay for so many Black workers disproportionately harmed during this pandemic? […] Why would DCH1 management call the cops on us when we went on Safety Strike demanding coronavirus protections at our warehouse?”.

With a similar intent, in the context of the riots that are crossing the United States, a group of activists and employees of Amazon a few weeks ago mounted a guillotine in front of Bezos’ house in Washington. The request made is a wage increase of 100%: “if Bezos earns 4000 dollars per second, it is not clear why we cannot earn 30 dollars per hour instead of 15”. Since June 1st, Amazon has put an end to the hourly wage increase by granting a one-time “thank you” bonus of $500/euro for the month of June. In June, however, the virus was still raging violently, especially in the U.S., with more than a thousand deaths per day. Moreover, a news from a few days ago, Amazon has opened managerial positions for intelligence experts, who are asked to investigate against the “dangers” that threaten the company, first of all the workers’ organization. It is then clear that for Amazon this pandemic has been a great opportunity – an opportunity to increase profits and an opportunity to strengthen corporate discipline –, but its concern for the increase in the internal communication among workers and in their ability to fight, despite all the old and new rules, layoffs, intimidating attitudes, is still great.

In the introduction to the journal we asked ourselves “what is our way to Seattle?”. Today we can say that some indications, in the struggles of these months, have emerged. If the pandemic has shown that wage increases can be decided overnight directly from Seattle, this means that the field of a transnational struggle for wage has opened up more clearly than ever before. If Amazon has the opportunity to raise wages for all overnight, why not to fight to introduce an equal wage for all warehouses, which would contrast Amazon’s claim to decide from above the price of health and time? If the standards of productivity have revealed all their unhealthiness and their functioning as risk factors, with or without the pandemic, the question is how to take up the knowledge that the struggles of these months have produced to advance a common claim of health and safety. It is also clear that it is necessary to avoid that the tools created to guarantee conditions of safety in the warehouse become another tool of control and to make sure that they become a chance to increase the communication between colleagues inside the warehouse and between the different warehouses, inside and outside Amazon. For those who doubted that the transnational organization was the way to gain more power and make the common claims heard to the giant of Seattle, these last months brought a clear answer. After having scared Amazon, the time has come to enlarge and deepen the fight to strike it. These are the issues that need to be addressed now and which, we think, should be at the center of the next Amazon workers’ meeting in Lille on the 25th-27th of September and towards the transnational strike in occasion of the upcoming Black Friday.