by TRANSNATIONAL SOCIAL STRIKE PLATFORM

Earlier this summer, on June 28 – 30, the 7th meeting of TSS Platform took place in Tbilisi, Georgia, organized thanks to Solidarity Network. This was the first time that the Platform went outside of the borders of the European Union. We encountered there new questions and new challenges facing the transnational struggle. At the time of our meeting, Tbilisi was shaken by protests against the government and its alleged pro-Russian positions. The protesters’ enthusiastic defiance against Russia mirrors in some way earlier manifestations in Ukraine, with passionate waving of flags that attest to the preferred allegiance: to the EU and even the US. While focusing on Russian influence, the protesters are not facing directly the major internal social and labor problems of the country. The situation is indicative of a real shift. Georgia’s geopolitical position in respect to trade agreements and infrastructural projects, the diversions of the sale and purchase channels of natural resources, a new visa regime for migrant workers and the migration agreement with the EU — as Georgia moves closer to the EU, the country is hit by transnational transformations that impel even government opposition to take the shape of a conflict over the most favorable position for the country in the international scenario. A rhetoric of national development and geopolitical competition constantly hides a reality of transnational mobility and exploitation.

In this confused situation, still charged with a persisting anti-Soviet rhetoric, the EU somehow comes to entail a promise of freedom and the EU flags are wielded as a sign of change. A great deal of the discussion during the meeting — which was attended by metro conductors and ticket agents, social workers, welfare workers and nurses — focused precisely on the real effects of the integration process. What does it mean to get closer to the EU and what is the price of inclusion for those living in Georgia? How does this picture change when one brings in the experience of those who are living in EU member States? Starting from the strikes and struggles we have taken part in or worked in solidarity with, such as the ones of Amazon workers, nurses in Bulgaria, the dockworkers in Sweden, migrants in Italy, and the global women’s strike, we discussed together what Europe actually is, ‘seen from the inside’ — from the point of view of precarious workers, migrants and non-migrants, women and men. How are transnational transformations and geopolitical moves affecting the conditions in which people are put to work? Is there any way in which an EU-flavored promise of freedom can be used as leverage for actual worker power? As was made clear throughout the meeting, these questions have a specific context and history in Georgia, but involve all those who are asking themselves how transnational struggle can be conducted beyond the alternative between pro- and anti-EU.

Confronting the EU ‘seen from the inside’ with the EU ‘seen from the outside’, we reached two sets of conclusions, highlighted as meaningful both for old and new members of the TSS. The first one was expressed clearly by one of the metro workers active in the Ertoba2013 (‘unity’) independent union in Tbilisi: ‘they tell us that our problem is that we are underdeveloped, but this accusation does not take into account what development would really mean’. Europe is not a paradise of labor rights and democracy, as the supporters of the Association Agreement with Georgia say, but is characterized by exploitation, repression, and institutional racism. Making Georgia a business-friendly environment means producing the most favorable conditions for obtaining cheap labor and maximizing capital profit. But the discussion clarified that European countries are undergoing the very same process: labour and welfare reforms such as Loi Travail and Macron’s ordonnances in France, Jobs Act in Italy, “slave-law” in Hungary, strike ban in Sweden, Hartz IV in Germany, Loi Peteers in Belgium — are part of a common design to intensify the command on labour, further dismantle welfare systems, and extend the precarization of working and living conditions. It became clear, as one of the women who organized the demonstration on March 8th in Tbilisi, stated, that ‘Georgia is not unique, which is both fortunate and unfortunate’. Unfortunate, because it means that the EU is not the promised land that some want to present; fortunate, because this means that there is a chance to overcome isolation, and there is room for a transnational connection of struggles.

Secondly, we came to the conclusion that the EU project of turning Georgia and other bordering countries into places where labor is kept passive and ready to be exploited, both domestically and abroad, is as a matter of fact doomed to fail because of the strong presence of new experiences of organization and struggle that challenge the project of turning them into additional bricks in the European neoliberal factory. The meeting opened with a presentation of the metro worker strike, given by the director of Ertoba2013. Thanks to a hunger strike which depleted the conductors’ health, thus barring them from working, they successfully overcame the legal ban to strike and subsequently received what they demanded in the first place: overtime pay, night pay, and additional days of vacation. This was the first metro strike in the Transcaucasian region, and it happened against the formal impossibility to strike: its effectiveness attracted other members of the company and much public support, reinvigorating the trade union’s capacity and public trust in it. This experience raised a discussion on what it means to circumvent strike limitations: in the strikes and protests in Amazon warehouses in Poland, the strike limitations do not simply include a harsh legislation on strike, that demands a nationwide ballot in all the warehouses, in order to legally declare a strike. It also means that Amazon hires a lot of agency workers that are usually not unionized and can be dismissed at any sign of unrest. Furthermore, due to the company’s transnational organization, Polish workers are used as a mass of involuntary strike-breakers when German workers go on strike, because in case of interruption among German workers, Amazon assure that distribution throughout the German market goes on as usual, only from across the border. In relation to this, we highlighted the importance of last year’s meetings between Amazon workers from several European countries: something that has proven more useful than formal international trade union networks, because it addresses not simply the problem of how to build bridges between structures, but of how to start building common demands and a common vision even beyond one’s own organization.

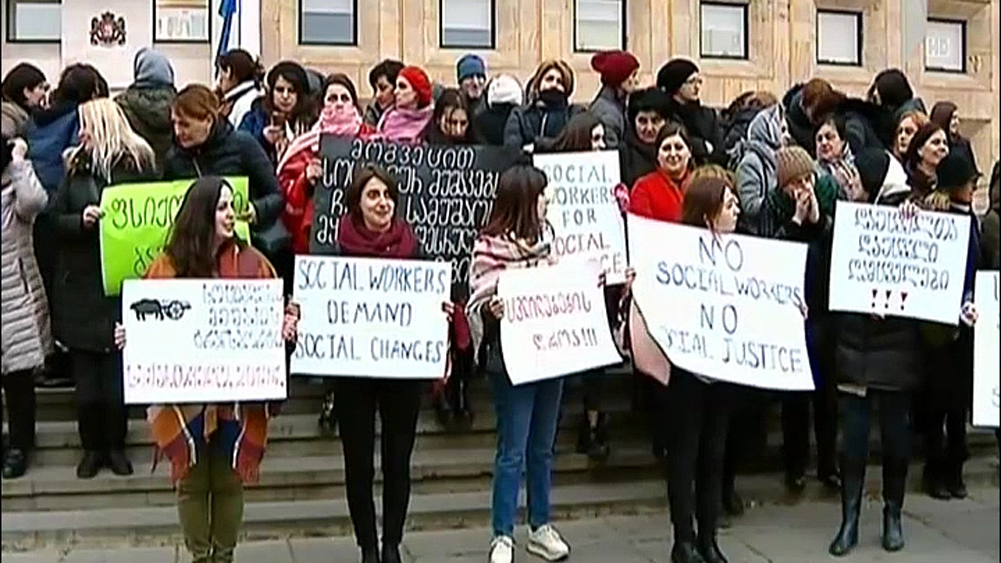

The winning experience of the strike of the metro workers accompanied the foundation of the first independent union in the country. In the experience of social workers and social welfare agents present at the meeting, instead, the relation between strike and organization was reversed. In fact, both founded their own independent unions only after having decided to go on strike. In a sector where workers are dispersed and isolated, a process of communication led first to a strike as a way to prove collective power. Only afterwards did the workers address the issue of creating a union as a bargaining tool. One important thing that came up in this discussion was the fact that the strike of social workers and social welfare agents was aimed not only at improving working and wage conditions, but also at protesting against the terrible situation of poor, if non-existent, social services. One important point that was made is that, rather than being an expression of ‘underdevelopment’, the extreme conditions of welfare in Georgia are also a consequence of years of market-friendly ‘reforms’ which paved the way to cuts in public spending, financialization of welfare and precarization: a stark example of what welfare means in neoliberal developed societies. The dismissal of basic services and the extreme individualization of benefits unveil the direction in which Europe is pointing.

The need to address at once the harsh working conditions and the living conditions of the recipients of the services made it clear that the challenge is not simply to legally gain the ‘right to strike’. We recognized that to overcome strike limitations means to find different ways of gaining social support from outside the workplaces and posing some key political issues that are not simply limited to the one strike action and do not simply stop after gaining better conditions just for some branch or some category of workers. The capacity to strike is not simply a technicality but concerns the possibility of asserting a collective power. This last element came up very clearly in the discussion around the global women’s strike: at stake there is precisely the possibility to use the strike to refuse sexual violence and the position women have in society and social reproduction, in spite of legal limitations and union affiliations. The experience of the women’s strike helped also in raising unavoidable issues for any struggle against exploitation: how can women strike if they are working isolated in houses, abroad, as is the case of hundreds of thousands Georgian women working in the EU, or in our country? How can the fact that women have a double workload, at home and at work, be properly addressed? How can we strike against the fact that women’s bodies are used in the international markets as in the case of surrogacy? In addressing this problem, the growing women’s movement in Georgia, as in many other countries, is currently marking a turning point in respect to a liberal kind of feminism that has never been able to connect the struggle against women’s subordination with that against a more general system of exploitation. In Tbilisi, as all over the world, the belief that the one cannot be fought without fighting the other is taking roots.

The meeting in Georgia reminded us once more that the transnational arena is where processes and struggles can be seen not as isolated and localized eruptions of discontent, always resulting from particular conditions, but as part of a transnational movement of struggle that is currently building a common language and a common vision. For pushing this process, it is necessary to recognize that Europe emerges as a complicated field of struggle. Seen from Europe’s Eastern fringes, two things are clear: that no way back is possible — there is no welfare state to regret, no social-democratic compromise to painstakingly restore; and that any unidirectional understanding of what Europe means today — either a neoliberal stronghold to destroy, or a land of rights and opportunities to be accessed — is only a way to remove existing and possible struggles from their real potential as elements of a transnational movement. The EU fringes seem to be the best stance from where to see the challenges awaiting a transnational movement of struggle, as places of stark transformations and of signs of unrest, and to discuss how to practice Europe as a field of struggle, without being stuck in the well-known alternatives. This we understood in Georgia, and this we aim at keeping discussing in the following months, to continue to produce political communication with a transnational scope.